An international team of astronomers has made a significant breakthrough in the study of one of the Solar System's most enigmatic planets – Uranus.

Utilizing data from the Hubble Space Telescope, researchers were able to determine with unprecedented accuracy the rotation speed of the planet's inner region.

The precision of the new measurements exceeds previous estimates by a factor of 1000, according to NASA's report. Their findings have been published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Previously, scientists relied on rotation speed estimates made back in 1986 during the flyby of the Voyager 2 probe.

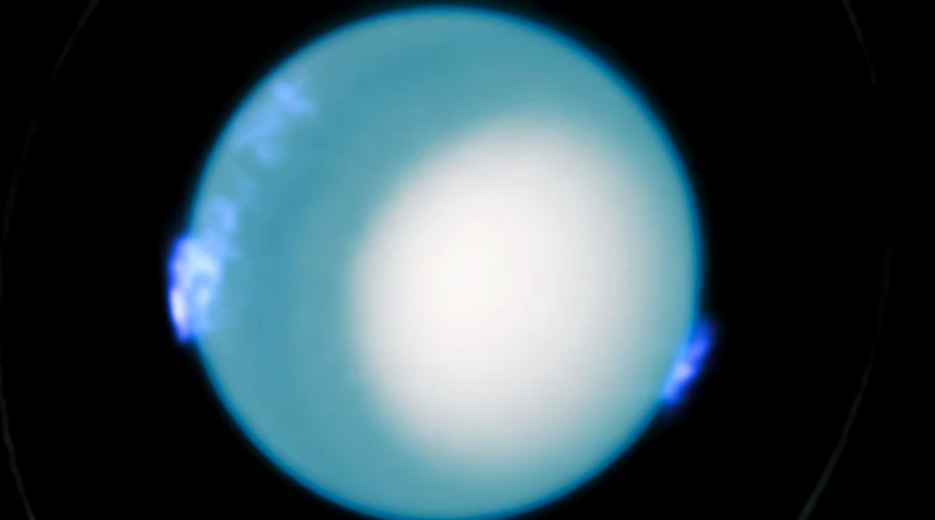

However, over more than a decade of observing the aurorae on Uranus with Hubble, the telescope regularly captured the planet's ultraviolet glow, allowing for the creation of magnetic field models that accurately reflect the changes in the magnetic poles' positions over time.

Unlike the auroras on Earth, Jupiter, or Saturn, the auroras on Uranus behave in a highly unpredictable manner. This is attributed to the planet's magnetic field being significantly tilted and offset from its rotation axis.

This new approach has shown that Uranus completes a full rotation in 17 hours, 14 minutes, and 52 seconds – which is 28 seconds longer than previously thought.

The new results provide a better understanding of Uranus' unique magnetosphere. As a result, researchers have not only refined the planet's rotation period but also established an important new coordinate system that will serve as a reference for scientists.

"Our measurement not only creates a new reference point for the planetary science community but also addresses an old problem. Previous coordinate systems based on outdated rotation periods quickly lost accuracy, making it difficult to track the positions of Uranus' magnetic poles.

With the new longitude system, we can compare auroral observations made over nearly 40 years and even prepare for future missions to Uranus," explained team leader Laurent Lamy from the Paris Observatory.

Earlier, the James Webb Telescope captured polar auroras on Neptune for the first time – the farthest planet from the Sun. Scientists have been trying to observe them since 1989.